Case Study

Reflecting from a distance

Ruminating on a personal locus of composition

In this section the work and its journey, from compelling notes in my mind to a fully scored musical work, are deliberated upon through the lens of time and distance. In these reflections, I do not cast aside the personal and my journals speak loudly here and describe actions, questioning and angst and, in doing so, they provide a unique insight into the compositional process.

Background

The endeavour here is to take the story which is My Sister's Tears and, given the time since, and interrogation that has ensued, seek to reflect on the compositional decision-making process. It is not meant to provide a measure of the musical quality of the work (that is for others to do) or to locate it amongst the canon of contemporary wind orchestral literature, but more so to allow the reader to be privy to the reasons behind the decisions taken and to place this discussion side by side with the more discursive style of my journal writing and autoethnographic narrative I have just shared.

This section is based on several different journals. There is the transcript of a recording done at the commencement of this research process. It is a quite confronting account of reflecting on the sketch itself, precipitated by questions from colleagues. It can be accessed under the title, "Reflection and Description". Edited extracts of recordings I made during the scoring of the work are also utilised. They can be located here as "Process and thinking" and "Process and Doing". Then there is the final review journal for My Sister's Tears, something which encapsulates much of the above and provides other reflective insights into the work and its genesis. Much of what is now reflected on is also evident in the preceding narrative which is found in the case study which I consider to be a story worth telling.

Composers over centuries have sought to connect their feelings with the feelings of the players of, and the listeners to, their music. Presenting my work in this manner may well inform the conductor and provide a more intimate perspective on My Sister's Tears. It may well suggest ways in which they may intersect with it and other pieces from my output by contextualising matters in a particular manner.

The blank page

Previously I have reflected on how I sketch a work; how it seems to come upon me more or less. It is different when I sit to score the piece. As I write the score no note is placed on the page without being proceeded by considerable intellectual and emotional rumination. Possibly the blank page of manuscript in the sketch has its precursor in the blank page of thought and feeling. Life's experience scrawls on the blank page. The blank score manuscript is different and my process (described in the journals for My Sister's Tears and Jessie's Well especially) becomes more methodical.

Experience is the mine into which emotion and intellect swing their picks. That experience is the lived human experience which arguably propels the desire to write, and the intellectual background, the grammar and syntax of music theory and compositional study, through which the human experience finds its voice.

The page is blank as the work forms in the heart and the mind. The page begins to be filled in as the ideas manifest themselves. Most often it is done quickly and assertively, though, at times, tentatively and more carefully when there is some hesitation or a fork appears in the compositional road. Consider the sketch and see how the pencil flies across the page to sketch the ideas quickly and comes back for more consideration and review.

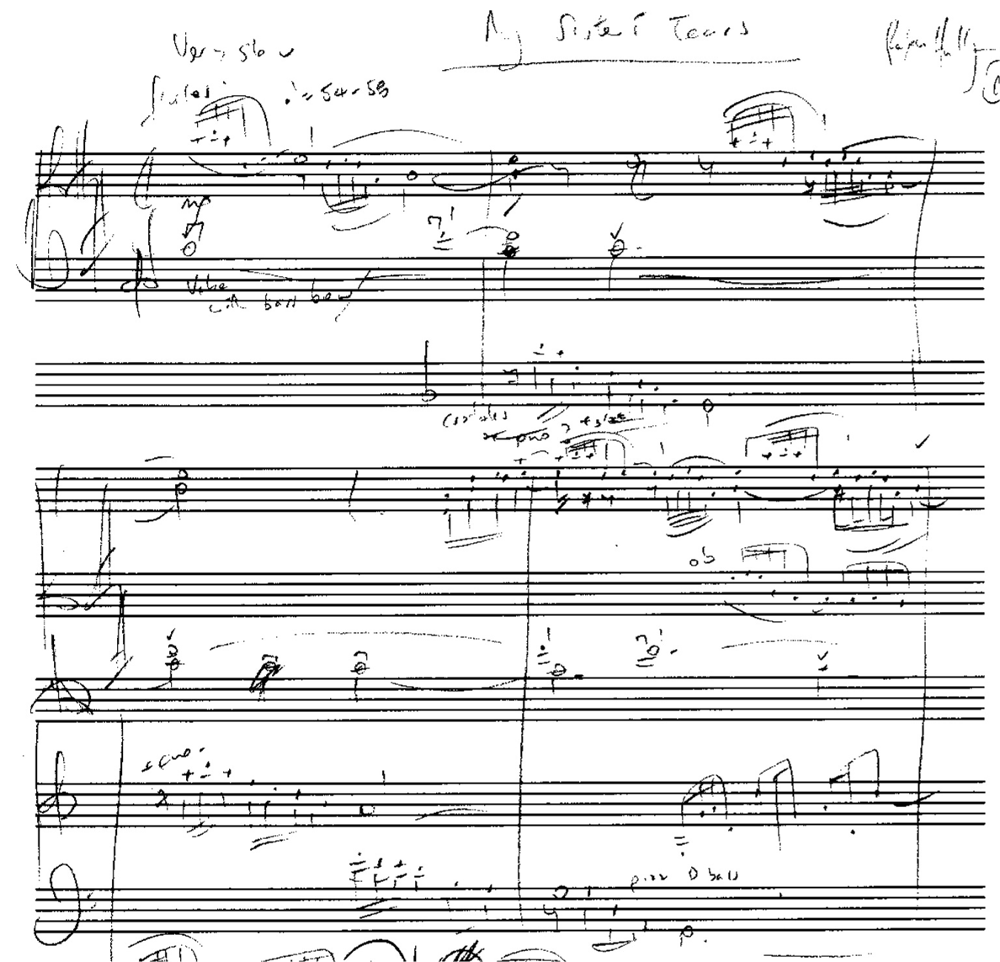

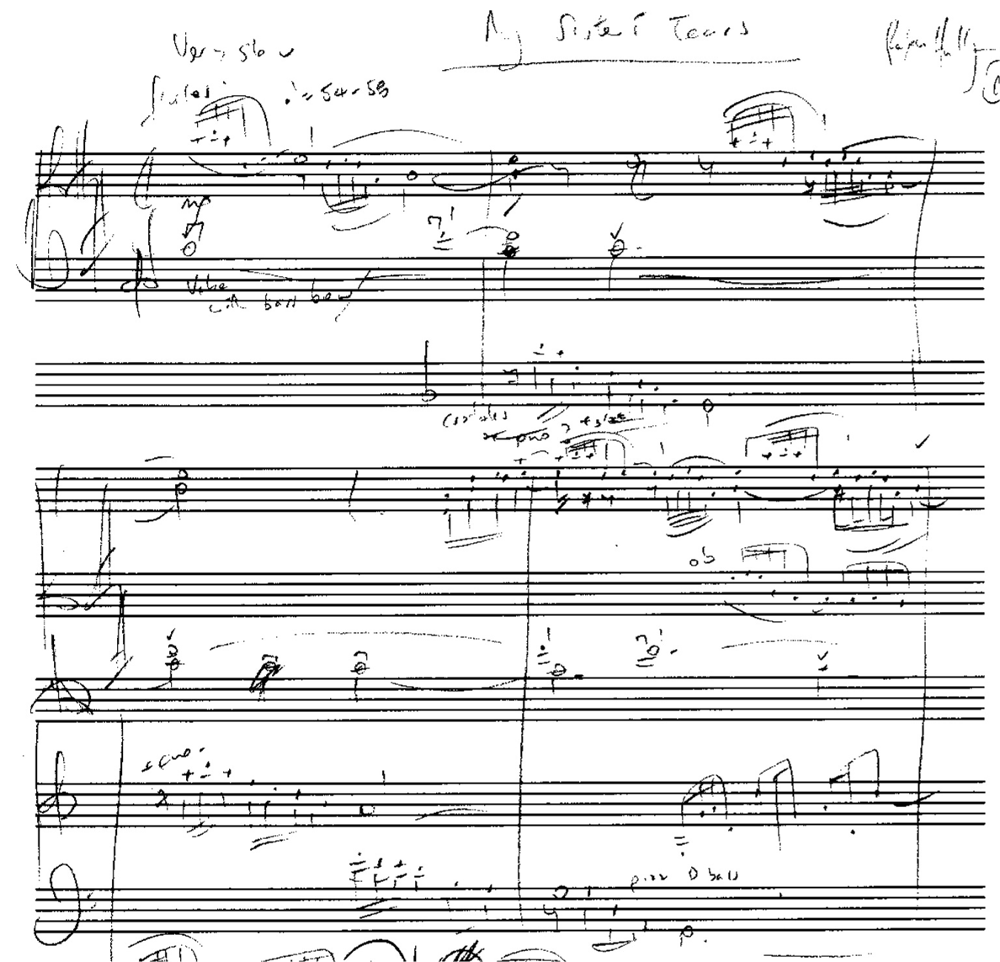

An example from can be found in the first page of the sketch of My Sister's Tears. (Ex. 1)

See how the melismastic ideas are quickly constructed and the darker pencil of review comes back to provide the clarity required for scoring and player's security. There is further evidence of this in the opening bars but what is more telling there is the sense of tonal bipolarity. "The beginning is floating around D and A major." (MST Review journal)

I see this as the manifestation of the human experience vivified through musical skill. For the

...opening is...dancing and floating...It needs the ephemeral qualities of the tinkling percussion and piano...The fading in and out of sounds which can be so beautifully represented on those instruments...an almost ballet-esque essence in the beginning here...I can understand my thoughts about my sister and her dancing classes but it's more the ephemeral and the floating...See how high it sits in the general register of the ensemble (MST Review journal).

This is the lived experience both in emotion and intellect for, on reflection, what has happened here is that delicacy of line is complimented with efficacy of orchestration and simple note choice to produce the ephemera desired.

The selection of tones common to D and A majors and a review of the utilisation of them, displays how tonal gravity pulls at the sense of being in A or D. Bars 1-3 could be in either key and eventually bar 4 introduces a G in the bass which turns the tonality more comfortably toward D major. Then bar 6 provides a possibility of becoming A major again, via a conservative secondary dominant effect.

All of this is dressed in the high register of the ensemble, though not of all the instruments. Flutes too high do not sound delicate but in this register they are. Bassoons are not low but play lower parts in the overall texture to give a sense of an upper end tessitura to the ensemble timbre. This is enhanced by the double bass also sitting higher in its register and yet producing the defining bass G mentioned above. I also consider the actual numbers of players as well when I write that:

...I've decided now there is no piccolo in this but there will be two flute parts, it's not just a flute part that could be played by multiple players - there's two flute parts with two or three players on each part...There is a thickness in sound that you can get from that and that is what I hear when its playing in my head so I know what I can take away from that to get a more transparent sound...I've written in the sketch times where its defined as being one player on each of those parts, so all of sudden you get the sense of an orchestral wind section as opposed to a concert band wind section which is consistently multiple players. (Process)

All of this, located in the melisma of the opening motif, produces the feeling alluded to in the journal entry cited above. These methods are utilised often throughout the work to give the same impression and even an allusion to a twirly dress. All of this comes onto a blank page from feeling distilled through technical skill.

Form and Structure

The sketch is used as an aide memoir. It provides the most concrete realisation of the concepts that are the genesis of the work. Arguably, in this form, the work is complete for me. The process after concluding the sketch is to realise it in a form that makes it accessible to conductors and performers – the conductor's full score.

The process, though, is not one of throwing notes onto the manuscript paper and a score appears. It involves constructing the manuscript prior to receiving the notes; making the way clear and unambiguous by adding to the blank score paper the keys and times signs, the changes in style and metre, and all indications regarding tempo and form (i.e. a del Segno or the like) – all the bars are written in and every musical descriptor is placed on the manuscript before any notes are written.

The whole idea of that is so I can just write, I don't have to think about how to fill in the lines or have an idea stifled as I turn the page because the manuscript's not ready. It's so I can just write when I start to score the sketch. (Process and Thinking)

Not only does it assist by ensuring the process is as unhindered as possible but the aide memoir comes into its own here as the guide for structure and orchestration. It also serves as a point of review because, as it is structurally complete for me, it allows me to sense proportion and reflect on colours and textures both before the scoring commences and during the process of orchestration. Drawing up the score paper is

…time consuming (but)…it helps me understand the architecture more and interestingly it pushes the compositional orchestrational idea as I'm drawing (the lines and instructions) and I'm looking at the sketch, working out the correct bar numbers and the placements. It is a point of standing back and it is "…good to…have a sense of architecture…" (Process and Thinking)

This process confronts matters of musical content also. At times the speed at which I get things down means I am not always accurate in notating what I want – occasional notes or tempo markings – and this aspect of the scoring, I assume because it takes time and is somewhat distant from creativity, prompts me to question some of the material on the sketch.

I talk of a changed "…note in the melody…around 27…when the melody slows down in its final part the original melody didn't reiterate the three notes at the beginning as an anacrusis…I'm sure (that's how) I heard it originally and so that's what I've altered it to." I speak about adjusting the tempo such as "…the 'accel' that happens after 40 somewhere, and…wonder whether it's a molto or not." (Process and Thinking)

When working on Jessie's Well I was reflecting on orchestration as I marked up the blank manuscript "…and (found that I was) revisiting the concepts of scoring." The process was at a place where "…I (had) not actually begun to score the work, only to mark up the pages to facilitate scoring later" (Jessie's Well journal summation). Matters such as this appear at a distance from the creative process but remain part of it. It's an enforced monitoring and review role I assume at this stage of the process.

This whole process also calls into question whether there is a system in my writing – a Hultgren method. No doubt there is and in my journals I allude to that method. In summary there are always four distinct stages – I am commissioned or am compelled to write; I allow the whole project to mull over in my mind and my heart; I begin to sketch when it is near completion, or complete, in my head and I write quickly and, given that I cannot play the piano, with no aural aids. The sketch comes out nearly complete and the scoring takes place very soon after. For example, My Sister's Tears sketch was commenced on February 14th, 2004 and completed on the 2nd of March. The full manuscript score was then finished on the "31st of March 2004 7.45pm" (annotation on the manuscript score). I am unsure if I might complete works more quickly if I did not have the responsibilities of a full time academic position. It may be that the time I am kept from completion might sharpen my reflection on the work as a whole.

Scoring and related matters

Above I reflected on the beginnings of this process of scoring. The sketch tells me much, but often the sketches' latent information tells me most. I find that what I have written in most detail on the sketch (instructions for the use of instruments and so forth e.g. flute here, clarinet there) is evidence of those portions of the sketch I am least sure of. It's as if the lack of information in the remainder of the sketch is evidence that I know what I want there. The excess annotations seem to be a guard against me forgetting or are the sign of places I have struggled over somewhat. Such is the aide memoir again.

I asked myself, "I wonder how many people think that composers start at the top left hand corner of the page and work their way through" (Process and Doing). I often process the score that way as I work as a conductor even though I am aware the composer hasn't necessarily made it in that way. My process is a whole, a complete activity that does not involve methodical steps from one bar to another, rather, it is a more like moving across and around the page.

On tape I talked about the tinkling nature at the beginning…reflecting on the fact that it might be my sister dancing or whatever. But what makes it tinkle is the percussion, the piano sounds, the flutes are the flowing tulle of the dance costume (is that assumptive?), but the tinkling, the lightness comes from the percussion, I believe. So that's actually where I've started. I've haven't started at the top of the page – I've started right at the bottom with vibraphone, glockenspiel, crotales and with piano, and now I'm going to deal with flute lines. (Process and Doing)

My decisions here are based on my acoustic experiences as a composer and conductor. I note that, "...no dynamics (are) marked in the sketch but I'm instantly writing them in the score" as the memory of aural imagination is jogged and tussled, as opposed to the 'guarding against forgetting' concept I note above. With years of conducting influencing me, I find my thinking, as I score the piece, is influenced and that "...everything is coloured by experience." How often

...the piano players...given to me as the conductor in the wind orchestra have been international students of dubious capacity (in ensemble playing). That is affecting the way in which I note the dynamics here - I'm actually upping some of the dynamic levels in here because they never project the sound. I can wave my hand at them in an inviting or a threatening way and they just play like they are sitting in their studio - there is no sense (from them) of projecting the sound yet the piano, here, is an integral part of this texture and it should be present. (Process and Doing)

The "leaping around on the score page" continues. Illumination of the ideas from the sketch is palpable as "...predominant lines are being drawn in on the score as they are drawn out of the sketch, intuitively. Then, as I move further I'm saying, 'Okay, how can I balance that line so it's complemented and not covered'? These are not random occurrences for "...this process is repeated over and over." (Process and Doing)

On occasion, time may be an adversary but what is taking place demands time be my ally. "It's taking forever..." to move along for it has taken forty minutes to move from the first note to bar 11. There are few notes but much to scratch my chin about but "...I love this process" (Process and Doing). There is occasional indecisiveness but it is more often reflection and review and ensuring that the instructions I have given myself, those ones I reflected on above about being unsure, are what I did indeed desire.

What I know as a composer is also informed by my experience as a teacher and as a professional trumpet player. I am aware from both sides of the podium and the manuscript paper. (The love of the process I allude to is infected by the love of playing. As a conductor, the output of the process, the new work I am performing, is similarly infectious.) I am aware often of writing lines and noticing my fingers moving as if to render them on a trumpet. Notes are added conscious of the player questioning a note length at the end of a phrase and I am determined to assist them, and the conductor, to realise that moment artistically.

Throughout this activity, the decision-making on all manner of musical questions, I am still involved in the work and its story via the process of realising it onto manuscript and then, eventually engraving it on a computer. At one stage I consider that

...the physical act of touching the paper makes me wonder about the digital domain. I am picking up each score page and thinking about it and turning it over and looking at what comes on the next page. It is like the pages have a life and a connection with each other. I know they are inanimate but the story written on them is not! (MST Review Journal)

Importantly, the action of scribbling on the sketch, and the response to it, are both tangible and visceral. Making the music real on the score manuscript page requires a great deal of me, even when I am not aware of it. Doing so confronts my decisions or draws me to make them, as the following demonstrates.

I...use a process when I'm scoring when...I put a bar's rest in front of the first entry of an instrument and then when their entry is finishes I put a bar's rest after the last note they play...I don't put rests in every measure, and what it makes me do is look to see if I've actually forgotten something or something should have entered, when I compare across the score. For example, I found out, I've just left out the 3rd and 4th horns in something and it's because I went to check those bars' rests. That is like the reflection on architecture I made on drawing up the score. It's a check; just making sure I have done everything. (Process and Doing)

The capacity I have to make the orchestration work challenges me as well. Mulling over bar 20

I started to get...a little 'clever' and wanted to score more instruments in; more voices. I think this is because I could. I know how to do it; I can balance it and 'colour' it and all that stuff because I'm a reasonable orchestrator. (Process and Doing)

There is a constant battle inside me to not write all that I can just because I know it will work. I most often battle with the "safety" of cross-cueing or over–orchestrating to cover the fallibility of solo players and lightly scored sections. Yet I must give vulnerable lines to players, for this story telling is a vulnerable act.

As the scoring proceeds I am very conscious of what can sound less than satisfying. When approaching bar 59, what "...I am trying to do is get the beautiful sounds of the saxophones to accompany the oboe. That's fraught with danger because, if it's bad oboes and bad saxophones there is hardly anything worse in the world, is there!" (Process and Doing)

That awareness of over–scoring, of adding too much colour, that I alluded to above is constantly before me. I ruminate over that and endeavour to not fall into that trap.

I'm trying to keep the brass out of it because the woodwinds haven't had much to do - it's very brass heavy so far...(and then)...there's hardly any percussion in this...I've taken out the cymbals which I would normally use in a big crescendo...There is no need to do that. Yet, I still wonder about what I might do to spice it up. No, not spice it up; add more colour to the sound at 68. Do I need too? I wonder whether the simplicity of the melody and accompaniment needs a richer texture in the orchestration; will the percussion need to do something? (Process and Doing)

I chose not to add the extra percussion, or to "...over-orchestrate....plain, melodic material, simple accompaniment, and simple counterpoint...(the) decision's made and it's what I wrote in the first place. I'm quite pleased about that."(Process and Doing) Intuitive decisions again; first choices in fact.

I choose to "cut and paste" in the old fashioned way by photocopying the first "...two pages because the beginning, the first 8 or 9 bars, is re-stated and I'm not going to write it all out again." I am sure of this and it leads comfortably into the coda where the

...ending needs to have a little more of the beginning and I've played with it a little bit - with the sketch from 112 to 118 will show how I played with it just a little bit...it has to tinkle just that little bit more. (Process and Doing).

What in fact happens is that the beginning ideas blend into the colours of the chorale evident not long after the work opens, and which returns in a form to conclude the piece. "Here the music seems to come together to speak its final farewell and allow itself its final remembrance." (MST Review Journal)

Even the melismas are more scalic and not as leaping around and when they come back like the beginning, they're more finely structured - they don't leap as much - they leap a little bit, but not much and then it just...comes to rest. (Reflection and Description)

I've come down (from having dinner) and in the last 20-25 minutes I've finished the piece. I've just that little bit to do; I'll go through and have a look at some things...the last check of things. I'm quite happy with the way it looks so far. There's a couple of balance things that I'm not sure of and I'm a little concerned about how the piano thing will go - I guess it's the conductor's role really. All finished! (Process and Doing)

I am unsure how long the work in embryo, the subconscious considerations and rumination over it, took to be finalised so that it made itself known to me. The wondering and reflecting on my sister's death that lead to the act of composing took much longer than the sketch itself I'm sure. As noted above, I began writing the sketch itself on the 14th of February 2004 but the process of completing the manuscript score itself didn't take place until March of that year. Having prepared the manuscript paper - no more than half a day's work - it took all of the 31st of March, a very long day but only one day, to place all of the dots on the page and make the story into a form that comes ever–closer to being made available to tell.

The final process of engraving on the computer is the most mundane for me. I would happily hand it off to a copyist but I find it is often the final stage of review - checking note lengths, refining rehearsal numbers and so forth - and so I am becoming more comfortable with that mechanical activity and finding it less onerous over time. It allows me to ensure that what I give to the conductor and the ensemble is the best I can offer for their use.