Case Study

Reflecting on

Reflecting on the context and the process

What makes me write music?

I can describe what I do as I compose. Writing these words about Heather and her suicide makes me want to go into sanitising mode; a mode of 'academic talk' that gives distance and makes matters less painful.

Look at the journal where I begin to discuss scoring and orchestrating; consider the parts of the first draft of this dissertation where I become 'academic' and see what I mean. Even look back at my other endeavours, such as my Master's study, to understand why I compose and what I am searching for and you will see that just explaining how I compose does not illuminate why I immerse myself in the manuscript and an empty room.

Looking into my feelings may expose matters fully. Of My Sister's Tears I noted that:

I wrote lots of it in Melbourne - well, no I didn't, probably the first bit of it.

Um,

I heard the tune...O.K.

where did it come from? I had a terrible dream about Heather..... a

terrible

dream...

Um...

and I couldn't save her and I held her in my arms, I wiped her tears and they wouldn't wipe

away,

and I wiped the blood on her and it wouldn't wipe away...

and I couldn't save her....

and I heard the tune, after the dream sometime, I heard the tune which is the chorale song-like

thing that's the main part of the piece. What were my thoughts? I just had to write; I mean

there

was no thought that this represented that or that represented that. Coming back I can say "well

this

tinkly thing at the beginning could be Heather dancing when she was a little kid" - but that's

the

conductor...that's....there was no consciousness of that??? I don't know what guides my pencil

when

I write. (Reflection and

Description, 2004, p.

2)

Some months later, as I prepared for my doctoral confirmation I rehearsed My Sister's Tears with the Conservatorium Wind Orchestra. The confirmation presentation was not like a normal seminar by a doctoral candidate. My desire was to have my music heard, not only talked about. Therefore the work, along with another of my works for developing musicians, was presented for the first time to group of family, friends and colleagues as part of the confirmation event. That performance activity was then followed by the normal seminar.

I found the preparation for the performance mode of confirmation a little unsettling. On the podium rehearsing the work, as I explained the dissonances in the piece, and the sadness or angst they portray, I became upset. This was not 'music', like I rehearse every week; this is my story about Heather. It is not maudlin or weepy but quite sad nonetheless.

So I drew in my breath and I became the narrator. It is my story still, Heather's and mine really - but I have now become a biographer and not an autobiographer.

I think and ruminate about orchestration in a way that lets me tell the players how to make them biographers too; the same with dynamics and articulations and the other 'stuff' of the musical page.

It's just code though. It's just a medium to transfer feeling and meaning.

It is reasonable to assert that the feelings behind the processes are wedded to the context of its intellectual realisation. When I finished the work and took it to rehearsal I found it so difficult to tell the players about it. I tell stories all the time, I am a raconteur, but this was different. How do you walk into a rehearsal of a university ensemble and talk about suicide, especially given that age group is over represented in suicide in the community? You do so with great trepidation and consideration. These may be 'at risk' kids. I liked how it sounded and I was not surprised with my reactions or that of the players.

As I stood in front of them, I did what I did on the night I found out about Heather's death, I drew in my breath and I became the third person orator and their protector.

As the rehearsal proceeded I became less afraid; some saw me weep a little at one stage. Their eyes asked me what was wrong.

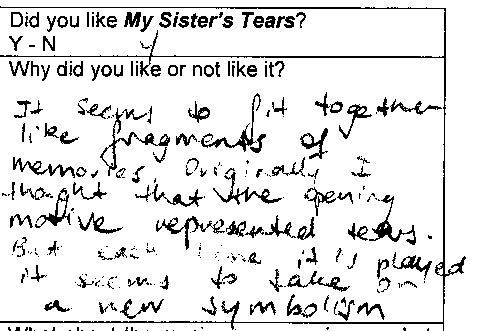

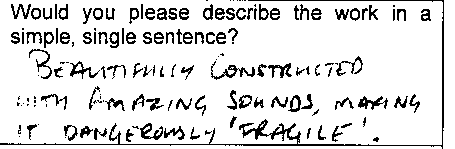

The dissonance was more real than my mind had heard; the flowing melismas more reminiscent of a beautiful little girl than a perplexed adult. Those lines began to infect the feeling of the players too. Students said:

Such comments lead me to ask, is this music, or is it story telling? The medium is music and the medium is giving meaning to the players as we rehearse.

After they began to master the basic material and could come to terms with the musical as well as the technical demands, I decided to tell them what it was about. A risk, yes, but if I didn't tell them I would be living a lie.

I always explain what I know about a piece and some were wondering why I hadn't told a 'story' yet. So, I spoke up:

"This piece is about my sister's suicide".

Some of them began to cry.

"I am so sorry to upset you."

We play some more and then the next week revisit the work.

"See, it twirls here - like her ballet skirt."

"Hear this chorale - it's my faith refusing to leave her to death."

"Listen to the trumpet - it's telling a story".

(A friend from church said that the trumpet is like the big brother calling to the little sister. I had never thought of that.)

I tell them the story of the work; of the dissonance, the joy of the flowing lines, the sadness of the emptiness in the scoring - I weep just a little, hoping I am not caught.

"See, the end. Diminuendo - see what it says; a niente, 'to nothing'".

I withdraw on the podium, I draw breath again, my eyes fill and that ache returns. Many of them ache with me, some tears too. Such delicate hearts!

It's so very sad...

...and it's in D major!